What have these people suffered

to become so beautiful?

By Ann Hauprich ©1992

The following is an excerpt from a speech delivered by Ann Hauprich to a

convention of Shriners at The Concord Resort on the evening of May 1, 1992.

A decade or so ago, a friend told me about the discovery of a tattered old tea towel inside a rustic cabin in Northern Ontario. Because the towel had been laundered so many times, it was faded -- and its design was hard to make out.

Upon closer examination, my friend was amazed to find that woven into the pattern was an inscription. It read: "What have these people suffered to become so beautiful?"

While I was fascinated with the profundity, its meaning was not entirely clear to me. It reminded me of a story I had read in a magazine a few years earlier in which film star Sophia Loren had been quoted as saying: "Unless a woman has cried, she cannot have beautiful eyes."

Because I was so young and had led a relatively sheltered life, I could not quite grasp what the tea towel scribe or Ms. Loren were attempting to share. I knew it was something infinitely more profound than the adage about beauty only being skin deep. Yet the link between suffering and beauty continued to elude me.

My understanding of these powerful quotations was not to begin for another two years when I received a proverbial "baptism by fire" into the world of burn victims and their caring support network of doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, counselors . . . and, working most quietly of all behind the scenes: members of The Shrine of North America.

The burn trauma unit where my two-year-old daughter was hospitalized following a severe scalding accident in 1984 was filled with faces and bodies scarred and disfigured beyond belief. Yet the longer I remained in the company of these burn patients, the more I witnessed their incredible courage, determination and inner strength -- the more beautiful they became in my eyes.

Most striking of all over these past several years has been the transformation of my own child from an ordinary little girl to an extraordinary young woman.

To me, she exemplifies what the Rev. Robert Schuller means when he talks about "turning your scars into stars."

Only a half an hour before my daughter's accident on the night of February 4, 1984, I had been giving her a bedtime bath. A girlfriend of mine named Andra, happened to be visiting that evening, and she and I were giggling, as young mothers often do, about the things strangers had said to us about our children in places like McDonald's and Burger King as well as at playgrounds and shopping malls.

Her two little boys were fair-haired to the point of resembling albinos and people always wanted to know about their ancestry -- which happened to have been Scandinavian. Strangers were also impressed that Andra managed to keep her boys impeccably groomed, despite their often rambunctious behavior.

I, on the other hand, was constantly hearing that Tara,

who was tiny for her two years and sported a head of long, thick, ringlets,

looked like "a miniature Shirley Temple" or a "Shirley Temple doll." Countless

strangers had advised me to enrol her in modeling school while others urged me

to have her audition for television commercials. "That child is gorgeous. She is

absolutely perfect!" they would insist.

I, on the other hand, was constantly hearing that Tara,

who was tiny for her two years and sported a head of long, thick, ringlets,

looked like "a miniature Shirley Temple" or a "Shirley Temple doll." Countless

strangers had advised me to enrol her in modeling school while others urged me

to have her audition for television commercials. "That child is gorgeous. She is

absolutely perfect!" they would insist.

While I had always been flattered that people thought Tara was such a natural beauty, I told Andra that I hoped Tara would grow up to be admired at least as much for her bright, inquisitive mind and kind personality as she, no doubt, would be for her stunning looks.

It never dawned on me as I dried Tara's beautiful little face and tiny, flawless body with a soft, fluffy towel that her physical appearance might ever be anything less than perfect. I could not know that the next time Tara would meet a stranger in a public place, the stranger would gasp and cry out: "Oh my God! What's wrong with your child's face?"

People tell me that I shouldn't feel guilty about what happened to my daughter a half hour after that wonderful, carefree bedtime bath. They say, it was an accident. That accidents happen. They say I should be happy that Tara recovered as well as she did. That her face has healed miraculously -- that she is lucky the worst of the burn and skin grafting scars can be hidden beneath clothing most of the time.

And, of course, they are right -- about much of what they say.

Accidents do happen. But, they can also be prevented.

In Tara's case, I only left a kettle of boiling water unattended for a moment or two while I ducked out of the kitchen to tell guests in the livingroom that coffee would be ready in a second.

But it was long enough for Tara to sneak from her bedroom down the hall of our ranch-style house and into the kitchen.

It was long enough for her to push a step-stool across the kitchen floor over to the counter where a large electric tea kettle was boiling at full capacity.

It was long enough for her to mount the step-stool and to become entangled in the electric cord, pulling the heavy kettle of boiling water over on top of her as she fell on her back.

By the time I heard her bloodcurdling screams, it was too late. The near empty electric kettle was imbedded in Tara's shoulder. Her face and nearly a third of her 23-pound, 33" tall body had been scalded.

Although I had taken a First Aid class a few years earlier, shock and disbelief numbed my reflexes. I cried and began to shake uncontrollably as Andra's husband Peter whisked Tara into the bathroom and held her under a cold shower while Tara's father telephoned for an ambulance.

Watching half of Tara's face and much of her body turning bright red and blistering as she screamed and shook in fright and agony on that cold, snowy Canadian winter's night is a nightmarish scene I have never been able to erase from my memory.

I wept in the ambulance all the way to the Hamilton General Hospital in Southern Ontario. I had burned my hand while trying to free Tara from the electric kettle and kept holding it against the frosty cold window in an attempt to relieve the pain. But even then, I kept saying to myself: "What you are feeling is only a pin prick compared to what that little baby is going through."

Over and over, I relived the accident. If only I hadn't left the room. If only I hadn't turned on the dishwasher, I would have heard her pushing the stool across the kitchen floor. If only I hadn't invited guests that night, I would have been reading to Tara or singing lullabies when the accident happened. If only I had bought a kettle with a whistle, I might have had a warning. If only I hadn't kept a step-stool by the phone.

If only. If only. If only. But I had left the room. I had turned on the dishwasher. I hadn't stayed with Tara as I usually did until she fell asleep. I had not anticipated her return to the kitchen. I had let my guard down. I had been negligent. My child was suffering -- and it was my fault. I hated myself. If only I could turn the clock back and undo what had happened. If only. If only. If only.

Alas, there was nothing I could do. I could not even hold my baby and tell her everything would be all right. Her condition was so serious, I was not allowed to be with her in the ambulance. I was seated -- shaking, weeping and of no use to anyone -- in the front seat while she lay shivering beside an attendant in the back crying out for me. "Mommy loves you. Mommy loves you," I tried to tell her through the glass that separated us. But I don't think she could hear me.

I had hoped I could stay with Tara and hold her hand after we finally got to the hospital 45 minutes later. But no, she was whisked away by the burn trauma team. I could hear her calling for me from a nearby room where her emergency medical needs were being met and it broke my heart to be kept outside the room. I wanted so much to hold her hand.

All these years later, I still wish they had let me be in the room. There is nothing worse for a mother than hearing her child call her name -- and not being allowed to answer. I can't tell you how many other mothers of burn victims I've met since have echoed this sentiment.

One thing I remember most vividly as I waited to be reunited with Tara that Saturday night was being told that a social worker would be in to see me on Monday. "Oh, my God! They must think we're child abusers!" I had exclaimed.

As it turned out, the intervention by social worker Claudia McDermott turned out to be a Godsend during Tara's first hospital stay -- which lasted over a month.

Ironically, it was Claudia who tried the hardest to cheer me up and help me overcome my intense feelings of guilt so that I might play a more positive role in Tara's physical and emotional recovery. A play therapist named Ruth Ann Horwood also did much to help me as she did to help Tara through those difficult days. I will never forget the kindness and compassion of these two very beautiful women who did as much as any human can to make sense out of suffering. I believe their very human touch in a very clinical environment played a crucial role in Tara's recovery. The healing power of touch -- and prayer -- must never be underestimated.

Likewise, I must say that the doctors and nurses I remember with the greatest affection were the ones who treated Tara and myself as human beings rather than as "burn victim" and "negligent mother who allowed child to become a patient in this burn ward." Among the kindest souls I encountered was a resident plastic surgeon who had clearly been told to give Tara's father and myself the "worst case scenario" involving our daughter on the night of her accident.

We were told there was a possibility that the left side of her face (which was then bright red) might remain discolored for the rest of her life. There was no way of knowing how much the redness might fade or whether the texture of the burned facial skin would heal smooth or bumpy.

The other burns to roughly a third of her body appeared to be a combination of first and second degree in severity. It would take a few days to determine the full extent of the tissue damage. Some spots were eventually pronounced "full thickness" burns -- the type requiring skin grafting.

Although the nurses made it clear they did not like parents staying near children at night, I begged to be allowed to pass the night in a chair next to Tara's bed. She barely slept all night, and I was glad I could at least hold her little fingers and offer words of comfort, humming familiar, soothing lullabies until she dozed off again. Her body was a mass of bandages, and it was not until morning that the full reality of what had happened hit home.

Here in the light, I saw a face so red and swollen, I again experienced a numbing sense of shock. My little Shirley Temple look-alike was gone. In her place was a tiny stranger, with one puffy, swollen eye, a swollen ear and facial contours swollen and distorted due to inflammation. The entire left side was beet red. "Oh, Tara," I cried.

But Tara did not answer. In fact, three days passed before she would communicate with either her father or me. Was she angry or in shock? I'll never know.

What triggered her first flow of words was a wooden puzzle from the hospital's playroom which contained a piece cut in the shape of a tea kettle. "That tea pot fell on my head . . . it was hot . . . that man put me in the shower . . . it was cold. " That run on sentence was repeated about 25 times in succession. Telling us about it over and over seemed to make Tara feel better and play therapist Ruth Ann assured us it was a good sign.

It was also healthy, Ruth Ann said, when Tara applied bandages to her dolls and stuffed animals -- placing the bandages on the exact spots where she herself had been injured. She was always very careful of the dolls -- though a doll that resembled a nurse took some rough handling!

Tara's dolls always had bandages on their right legs, right arms, and their left arms with special care given when looking after the shoulder/chest and underarm. That's because Tara's right arm was initially bandaged from toe to upper thigh and Tara -- our little "roadrunner" refused to even try to walk at first. Physiotherapy was prescribed and her painful limp was restored to a healthy walk only after much forced stretching of the burned leg . . . and many tears.

Similarly, Tara refused to lift or stretch her left arm until after a skin grafting operation about three weeks into her hospital stay. Only after recovering from that surgery (which meant removing skin from her buttocks) was Tara able to use that arm without screaming in pain.

They say misery loves company, and Tara's placement in a room with a little boy named Jason turned out to be a blessing -- because his presence served as a constant reminder of how much worse off our family could have been.

Six-year-old Jason had suffered severe facial and hand burns when his house was gutted by fire. That was enough of a load for any little soldier and his parents to carry. And my heart went out to them. When I subsequently learned that Jason's three-year-old brother, Jeremy, had died in that same tragic house fire -- I realized that the cross my family had been given to carry was not so heavy after all.

Over and over during Tara's lengthy hospitalization and during subsequent outpatient visits to clinics at Hamilton General Hospital, Toronto's Hospital For Sick Children, and more recently at the Shriners Burns Institutes in Boston, I would be reminded of the adage: "I cried because I had no shoes until I met a man who had no feet." One need only read the wonderful passage entitled "Footprints" to know that when only one set of footprints appears in the sand it is because the Lord is carrying us.

Every time a new obstacle came up in the course of Tara's recovery, the Lord sent a "Highway To Heaven" or "Wonderful Life" kind of angel to help.

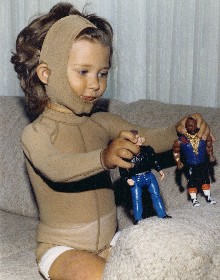

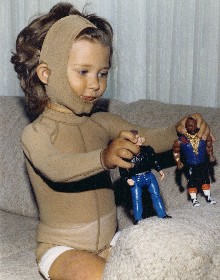

Take, for example, the JOBST compression suits we were told Tara

would have to wear 24 hours a day, seven days a week for about two years after

her accident. Cost of the physiologically engineered, custom-made garments

designed to control the hypotrophic scarring common to burn victims, was

estimated at $2,500. Our government-health insurance plan would cover only a

portion of the therapeutic suits. Since I had left the full-time work force to

care for Tara, there was no way we could pay for the suits -- short of selling

our home and using the proceeds.

Take, for example, the JOBST compression suits we were told Tara

would have to wear 24 hours a day, seven days a week for about two years after

her accident. Cost of the physiologically engineered, custom-made garments

designed to control the hypotrophic scarring common to burn victims, was

estimated at $2,500. Our government-health insurance plan would cover only a

portion of the therapeutic suits. Since I had left the full-time work force to

care for Tara, there was no way we could pay for the suits -- short of selling

our home and using the proceeds.

Worrying about how to finance these very necessary compression suits was the last thing we needed as we fretted over Tara's physical and emotional recovery. Enter Bill Boyd of the Rameses Shrine Temple in Downsview, Ontario with news that the organization would pick up the portion of the suits not covered by insurance. The intervention of the Ramese Shrine Temple during 1984 and 1985 was the answer to a prayer!

Squeezing Tara into those compression suits and facial masks every day, removing them only for bathing, and then squeezing them back on again -- was a daily trial. Adding to the stress of simply getting her into the tight suits was the reaction of strangers who saw her wearing them.

My initial response was to try to hide the suits under long-sleeved shirts and long pants -- even in 90 F weather. I cleaned the local department store out of its Holly Hobby style bonnets -- Tara had white ones, pink ones, blue ones, checks and floral prints. While this didn't totally eliminate stares and tactless remarks from strangers, it did make the masks and Jobst suits less noticeable.

Although I will always wish my daughter had been spared both the physical pain of the burns and the emotional pain linked to her scars, I must say that her ordeal has truly made her an extraordinarily beautiful person. Tara exudes a radiance, compassion, warmth and depth of personality that is extremely rare in 10-year-old girls.

When I look at her, I think of Sophia Loren's observation that "unless a woman has cried, she cannot have beautiful eyes" . . . and I wonder about the experiences that led that designer to add the words "What have these people suffered to become so beautiful" to his or her tea towel.

In closing, I'd like to share a verse I clipped from a magazine not long after Tara was burned. It is now yellowed and crumpled from being carried in my purse, but every time I read it, its message speaks to me anew of the contribution of The Shriners to burned children and their families.

It goes like this: "There are places in the heart that do not yet exist. Suffering must enter before these places come to be. This creativity of suffering applies not only to the one who suffers, but also to those who seek to lessen the suffering."

In working tirelessly to reduce the suffering of others, you, the members of The Shrine of North America, have shown the world what it is to be truly beautiful.

Thank you!

A decade or so ago, a friend told me about the discovery of a tattered old tea towel inside a rustic cabin in Northern Ontario. Because the towel had been laundered so many times, it was faded -- and its design was hard to make out.

Upon closer examination, my friend was amazed to find that woven into the pattern was an inscription. It read: "What have these people suffered to become so beautiful?"

While I was fascinated with the profundity, its meaning was not entirely clear to me. It reminded me of a story I had read in a magazine a few years earlier in which film star Sophia Loren had been quoted as saying: "Unless a woman has cried, she cannot have beautiful eyes."

Because I was so young and had led a relatively sheltered life, I could not quite grasp what the tea towel scribe or Ms. Loren were attempting to share. I knew it was something infinitely more profound than the adage about beauty only being skin deep. Yet the link between suffering and beauty continued to elude me.

My understanding of these powerful quotations was not to begin for another two years when I received a proverbial "baptism by fire" into the world of burn victims and their caring support network of doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, counselors . . . and, working most quietly of all behind the scenes: members of The Shrine of North America.

The burn trauma unit where my two-year-old daughter was hospitalized following a severe scalding accident in 1984 was filled with faces and bodies scarred and disfigured beyond belief. Yet the longer I remained in the company of these burn patients, the more I witnessed their incredible courage, determination and inner strength -- the more beautiful they became in my eyes.

Most striking of all over these past several years has been the transformation of my own child from an ordinary little girl to an extraordinary young woman.

To me, she exemplifies what the Rev. Robert Schuller means when he talks about "turning your scars into stars."

Only a half an hour before my daughter's accident on the night of February 4, 1984, I had been giving her a bedtime bath. A girlfriend of mine named Andra, happened to be visiting that evening, and she and I were giggling, as young mothers often do, about the things strangers had said to us about our children in places like McDonald's and Burger King as well as at playgrounds and shopping malls.

Her two little boys were fair-haired to the point of resembling albinos and people always wanted to know about their ancestry -- which happened to have been Scandinavian. Strangers were also impressed that Andra managed to keep her boys impeccably groomed, despite their often rambunctious behavior.

I, on the other hand, was constantly hearing that Tara,

who was tiny for her two years and sported a head of long, thick, ringlets,

looked like "a miniature Shirley Temple" or a "Shirley Temple doll." Countless

strangers had advised me to enrol her in modeling school while others urged me

to have her audition for television commercials. "That child is gorgeous. She is

absolutely perfect!" they would insist.

I, on the other hand, was constantly hearing that Tara,

who was tiny for her two years and sported a head of long, thick, ringlets,

looked like "a miniature Shirley Temple" or a "Shirley Temple doll." Countless

strangers had advised me to enrol her in modeling school while others urged me

to have her audition for television commercials. "That child is gorgeous. She is

absolutely perfect!" they would insist.While I had always been flattered that people thought Tara was such a natural beauty, I told Andra that I hoped Tara would grow up to be admired at least as much for her bright, inquisitive mind and kind personality as she, no doubt, would be for her stunning looks.

It never dawned on me as I dried Tara's beautiful little face and tiny, flawless body with a soft, fluffy towel that her physical appearance might ever be anything less than perfect. I could not know that the next time Tara would meet a stranger in a public place, the stranger would gasp and cry out: "Oh my God! What's wrong with your child's face?"

People tell me that I shouldn't feel guilty about what happened to my daughter a half hour after that wonderful, carefree bedtime bath. They say, it was an accident. That accidents happen. They say I should be happy that Tara recovered as well as she did. That her face has healed miraculously -- that she is lucky the worst of the burn and skin grafting scars can be hidden beneath clothing most of the time.

And, of course, they are right -- about much of what they say.

Accidents do happen. But, they can also be prevented.

In Tara's case, I only left a kettle of boiling water unattended for a moment or two while I ducked out of the kitchen to tell guests in the livingroom that coffee would be ready in a second.

But it was long enough for Tara to sneak from her bedroom down the hall of our ranch-style house and into the kitchen.

It was long enough for her to push a step-stool across the kitchen floor over to the counter where a large electric tea kettle was boiling at full capacity.

It was long enough for her to mount the step-stool and to become entangled in the electric cord, pulling the heavy kettle of boiling water over on top of her as she fell on her back.

By the time I heard her bloodcurdling screams, it was too late. The near empty electric kettle was imbedded in Tara's shoulder. Her face and nearly a third of her 23-pound, 33" tall body had been scalded.

Although I had taken a First Aid class a few years earlier, shock and disbelief numbed my reflexes. I cried and began to shake uncontrollably as Andra's husband Peter whisked Tara into the bathroom and held her under a cold shower while Tara's father telephoned for an ambulance.

Watching half of Tara's face and much of her body turning bright red and blistering as she screamed and shook in fright and agony on that cold, snowy Canadian winter's night is a nightmarish scene I have never been able to erase from my memory.

I wept in the ambulance all the way to the Hamilton General Hospital in Southern Ontario. I had burned my hand while trying to free Tara from the electric kettle and kept holding it against the frosty cold window in an attempt to relieve the pain. But even then, I kept saying to myself: "What you are feeling is only a pin prick compared to what that little baby is going through."

Over and over, I relived the accident. If only I hadn't left the room. If only I hadn't turned on the dishwasher, I would have heard her pushing the stool across the kitchen floor. If only I hadn't invited guests that night, I would have been reading to Tara or singing lullabies when the accident happened. If only I had bought a kettle with a whistle, I might have had a warning. If only I hadn't kept a step-stool by the phone.

If only. If only. If only. But I had left the room. I had turned on the dishwasher. I hadn't stayed with Tara as I usually did until she fell asleep. I had not anticipated her return to the kitchen. I had let my guard down. I had been negligent. My child was suffering -- and it was my fault. I hated myself. If only I could turn the clock back and undo what had happened. If only. If only. If only.

Alas, there was nothing I could do. I could not even hold my baby and tell her everything would be all right. Her condition was so serious, I was not allowed to be with her in the ambulance. I was seated -- shaking, weeping and of no use to anyone -- in the front seat while she lay shivering beside an attendant in the back crying out for me. "Mommy loves you. Mommy loves you," I tried to tell her through the glass that separated us. But I don't think she could hear me.

I had hoped I could stay with Tara and hold her hand after we finally got to the hospital 45 minutes later. But no, she was whisked away by the burn trauma team. I could hear her calling for me from a nearby room where her emergency medical needs were being met and it broke my heart to be kept outside the room. I wanted so much to hold her hand.

All these years later, I still wish they had let me be in the room. There is nothing worse for a mother than hearing her child call her name -- and not being allowed to answer. I can't tell you how many other mothers of burn victims I've met since have echoed this sentiment.

One thing I remember most vividly as I waited to be reunited with Tara that Saturday night was being told that a social worker would be in to see me on Monday. "Oh, my God! They must think we're child abusers!" I had exclaimed.

As it turned out, the intervention by social worker Claudia McDermott turned out to be a Godsend during Tara's first hospital stay -- which lasted over a month.

Ironically, it was Claudia who tried the hardest to cheer me up and help me overcome my intense feelings of guilt so that I might play a more positive role in Tara's physical and emotional recovery. A play therapist named Ruth Ann Horwood also did much to help me as she did to help Tara through those difficult days. I will never forget the kindness and compassion of these two very beautiful women who did as much as any human can to make sense out of suffering. I believe their very human touch in a very clinical environment played a crucial role in Tara's recovery. The healing power of touch -- and prayer -- must never be underestimated.

Likewise, I must say that the doctors and nurses I remember with the greatest affection were the ones who treated Tara and myself as human beings rather than as "burn victim" and "negligent mother who allowed child to become a patient in this burn ward." Among the kindest souls I encountered was a resident plastic surgeon who had clearly been told to give Tara's father and myself the "worst case scenario" involving our daughter on the night of her accident.

We were told there was a possibility that the left side of her face (which was then bright red) might remain discolored for the rest of her life. There was no way of knowing how much the redness might fade or whether the texture of the burned facial skin would heal smooth or bumpy.

The other burns to roughly a third of her body appeared to be a combination of first and second degree in severity. It would take a few days to determine the full extent of the tissue damage. Some spots were eventually pronounced "full thickness" burns -- the type requiring skin grafting.

Although the nurses made it clear they did not like parents staying near children at night, I begged to be allowed to pass the night in a chair next to Tara's bed. She barely slept all night, and I was glad I could at least hold her little fingers and offer words of comfort, humming familiar, soothing lullabies until she dozed off again. Her body was a mass of bandages, and it was not until morning that the full reality of what had happened hit home.

Here in the light, I saw a face so red and swollen, I again experienced a numbing sense of shock. My little Shirley Temple look-alike was gone. In her place was a tiny stranger, with one puffy, swollen eye, a swollen ear and facial contours swollen and distorted due to inflammation. The entire left side was beet red. "Oh, Tara," I cried.

But Tara did not answer. In fact, three days passed before she would communicate with either her father or me. Was she angry or in shock? I'll never know.

What triggered her first flow of words was a wooden puzzle from the hospital's playroom which contained a piece cut in the shape of a tea kettle. "That tea pot fell on my head . . . it was hot . . . that man put me in the shower . . . it was cold. " That run on sentence was repeated about 25 times in succession. Telling us about it over and over seemed to make Tara feel better and play therapist Ruth Ann assured us it was a good sign.

It was also healthy, Ruth Ann said, when Tara applied bandages to her dolls and stuffed animals -- placing the bandages on the exact spots where she herself had been injured. She was always very careful of the dolls -- though a doll that resembled a nurse took some rough handling!

Tara's dolls always had bandages on their right legs, right arms, and their left arms with special care given when looking after the shoulder/chest and underarm. That's because Tara's right arm was initially bandaged from toe to upper thigh and Tara -- our little "roadrunner" refused to even try to walk at first. Physiotherapy was prescribed and her painful limp was restored to a healthy walk only after much forced stretching of the burned leg . . . and many tears.

Similarly, Tara refused to lift or stretch her left arm until after a skin grafting operation about three weeks into her hospital stay. Only after recovering from that surgery (which meant removing skin from her buttocks) was Tara able to use that arm without screaming in pain.

They say misery loves company, and Tara's placement in a room with a little boy named Jason turned out to be a blessing -- because his presence served as a constant reminder of how much worse off our family could have been.

Six-year-old Jason had suffered severe facial and hand burns when his house was gutted by fire. That was enough of a load for any little soldier and his parents to carry. And my heart went out to them. When I subsequently learned that Jason's three-year-old brother, Jeremy, had died in that same tragic house fire -- I realized that the cross my family had been given to carry was not so heavy after all.

Over and over during Tara's lengthy hospitalization and during subsequent outpatient visits to clinics at Hamilton General Hospital, Toronto's Hospital For Sick Children, and more recently at the Shriners Burns Institutes in Boston, I would be reminded of the adage: "I cried because I had no shoes until I met a man who had no feet." One need only read the wonderful passage entitled "Footprints" to know that when only one set of footprints appears in the sand it is because the Lord is carrying us.

Every time a new obstacle came up in the course of Tara's recovery, the Lord sent a "Highway To Heaven" or "Wonderful Life" kind of angel to help.

Take, for example, the JOBST compression suits we were told Tara

would have to wear 24 hours a day, seven days a week for about two years after

her accident. Cost of the physiologically engineered, custom-made garments

designed to control the hypotrophic scarring common to burn victims, was

estimated at $2,500. Our government-health insurance plan would cover only a

portion of the therapeutic suits. Since I had left the full-time work force to

care for Tara, there was no way we could pay for the suits -- short of selling

our home and using the proceeds.

Take, for example, the JOBST compression suits we were told Tara

would have to wear 24 hours a day, seven days a week for about two years after

her accident. Cost of the physiologically engineered, custom-made garments

designed to control the hypotrophic scarring common to burn victims, was

estimated at $2,500. Our government-health insurance plan would cover only a

portion of the therapeutic suits. Since I had left the full-time work force to

care for Tara, there was no way we could pay for the suits -- short of selling

our home and using the proceeds.Worrying about how to finance these very necessary compression suits was the last thing we needed as we fretted over Tara's physical and emotional recovery. Enter Bill Boyd of the Rameses Shrine Temple in Downsview, Ontario with news that the organization would pick up the portion of the suits not covered by insurance. The intervention of the Ramese Shrine Temple during 1984 and 1985 was the answer to a prayer!

Squeezing Tara into those compression suits and facial masks every day, removing them only for bathing, and then squeezing them back on again -- was a daily trial. Adding to the stress of simply getting her into the tight suits was the reaction of strangers who saw her wearing them.

My initial response was to try to hide the suits under long-sleeved shirts and long pants -- even in 90 F weather. I cleaned the local department store out of its Holly Hobby style bonnets -- Tara had white ones, pink ones, blue ones, checks and floral prints. While this didn't totally eliminate stares and tactless remarks from strangers, it did make the masks and Jobst suits less noticeable.

Although I will always wish my daughter had been spared both the physical pain of the burns and the emotional pain linked to her scars, I must say that her ordeal has truly made her an extraordinarily beautiful person. Tara exudes a radiance, compassion, warmth and depth of personality that is extremely rare in 10-year-old girls.

When I look at her, I think of Sophia Loren's observation that "unless a woman has cried, she cannot have beautiful eyes" . . . and I wonder about the experiences that led that designer to add the words "What have these people suffered to become so beautiful" to his or her tea towel.

In closing, I'd like to share a verse I clipped from a magazine not long after Tara was burned. It is now yellowed and crumpled from being carried in my purse, but every time I read it, its message speaks to me anew of the contribution of The Shriners to burned children and their families.

It goes like this: "There are places in the heart that do not yet exist. Suffering must enter before these places come to be. This creativity of suffering applies not only to the one who suffers, but also to those who seek to lessen the suffering."

In working tirelessly to reduce the suffering of others, you, the members of The Shrine of North America, have shown the world what it is to be truly beautiful.

Thank you!